5 tips to create clarity.

Why are leaders and politicians never totally clear and what can they do about it?

By Edouard Gruwez,

Employees often complain that decisions are unclear, contradictory even. Yet their leaders are convinced that the plans are crystal clear. It’s just very difficult to make people understand, despite all communication efforts.

When I was a senior manager I used to think: “When people say my plans aren’t clear, what they really mean is that they don’t understand”. But I was wrong.

But could it be that the problem is not communication? That their strategies and plans really aren’t clear? Just do the test: ask 6 senior managers within one organisation what the strategy is. And don’t be surprised to get 6 different stories. Go in more depth with concrete questions. And don’t be surprised to hear utter contradictions. This has nothing to do with their individual communication skills. Their strategy just isn’t clear.

This lack of clarity isn’t limited to corporate life. Read a piece of legislation (I recently made an attempt at MIFID ii). It is often so unclear that expert lawyers debate for months on how to interpret the law. Why didn’t legislators make it clear in the first place? The same holds for doctors, researchers, journalists, teachers, and many others… It is the case for anyone working in an environment with high complexity, fast change, many uncertainties, or blurred information.

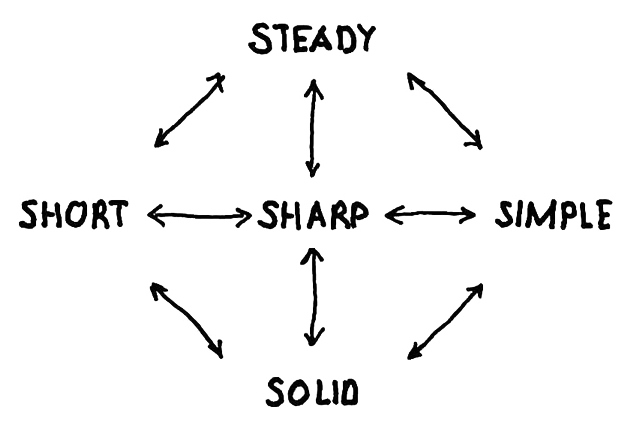

Being clear is finding a balance

Being clear requires optimizing your thoughts (and words) in 5 different dimensions: being Sharp, Simple, Short, Steady and Solid. But if you have too much of one, you will not have enough of the other: if you’re too sharp, you won’t be steady. If too simple, you won’t be solid. And if you are too solid, you are probably complicated and unconvincing. To be clear you need to find a balance. And this delicate balance can be different in every situation and for every audience.

1. Be sharp while embracing ambiguity.

2. Be short while embracing the need for detail.

3. Be simple while embracing complexity.

4. Be steady while embracing change.

5. Be solid while embracing uncertainty and emotion.

1. Be sharp while embracing ambiguity.

Your communication has to be razor-sharp. Your words must be precise, so that people clearly understand what you mean. You don’t want to be vague or blurred.

“In the landscape of extinction, precision is next to godliness”

Samuel Beckett.

But you don’t want to be too sharp.

Firstly, most things in life have some ambiguity. How can you be sharp when communicating about something ambiguous? If you want to be honest and credible, at least communicate about the ambiguity of your message.

For example: “Earth’s temperature is rising because of our use of fossil fuel.” This is a very sharp statement, but it denies the ambiguity: The average temperature is certainly rising. But there is at least some ambiguity about the cause. For sure physics and chemistry prove that more CO2 impacts the ozone layer and earth’s temperature. But one can also argue that the average temperature has known many fluctuations, up and down, and that today’s rise is but another fluctuation. And there could be other causes. So, a more correct statement would be: “Earth’s temperature is rising, and there are strong indications that burning fuel is one of the causes”. Without this addition, your statement is not robust and you leave the door open to critics. People with interests in fossil fuel can use this gap to undermine your credibility.

Secondly, your audience must be able to translate your words into their reality. This inevitably requires you to leave some ambiguity. Compare these two statements: “Driving petrol cars makes earth’s temperature rise” and “Burning fossil fuel makes earth’s temperature rise”. The first is sharper while the latter allows more people to translate the message into their reality. Which is the better statement? It’s depends on your audience.

A false feeling of achievement. Managers and politicians are often ambiguous for an entirely different reason. When they disagree, the solution is often found in “clever wording”. Something everyone can agree to. In fact that wording leaves enough ambiguity for all parties to (unconsciously) interpret the decision in their own way. It creates a feeling of agreement without anyone really changing his mind. Later-on everyone is surprised that implementation is difficult. They feel that others have put a spoke in the wheel or believe that communication was bad. But no one realizes that they never had a true agreement in the first place.

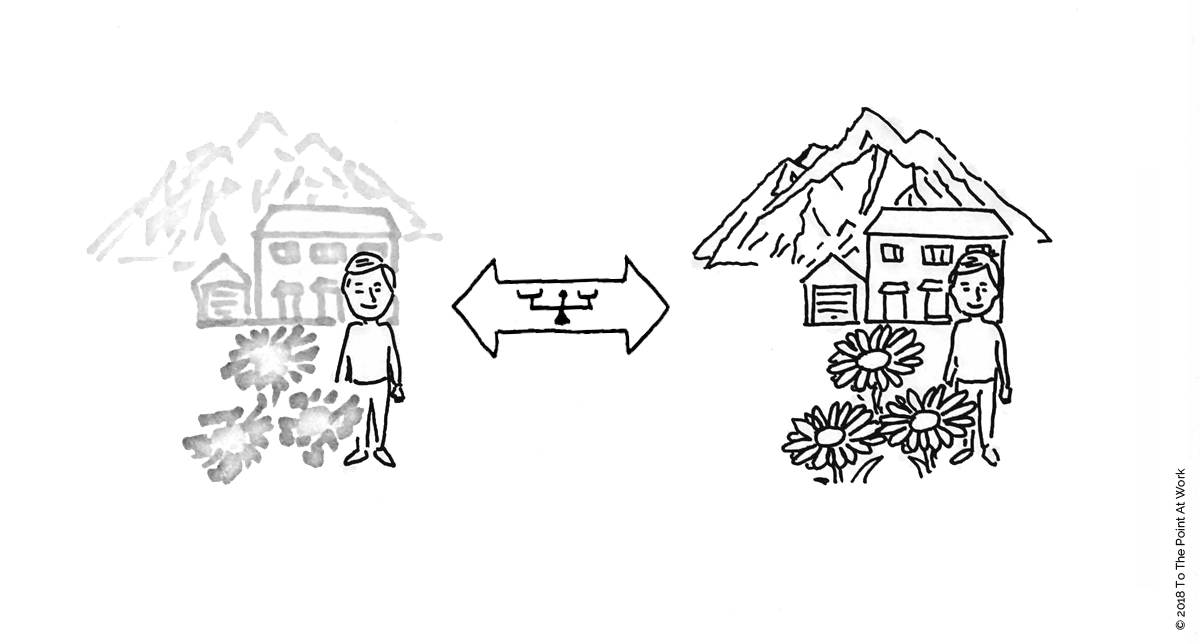

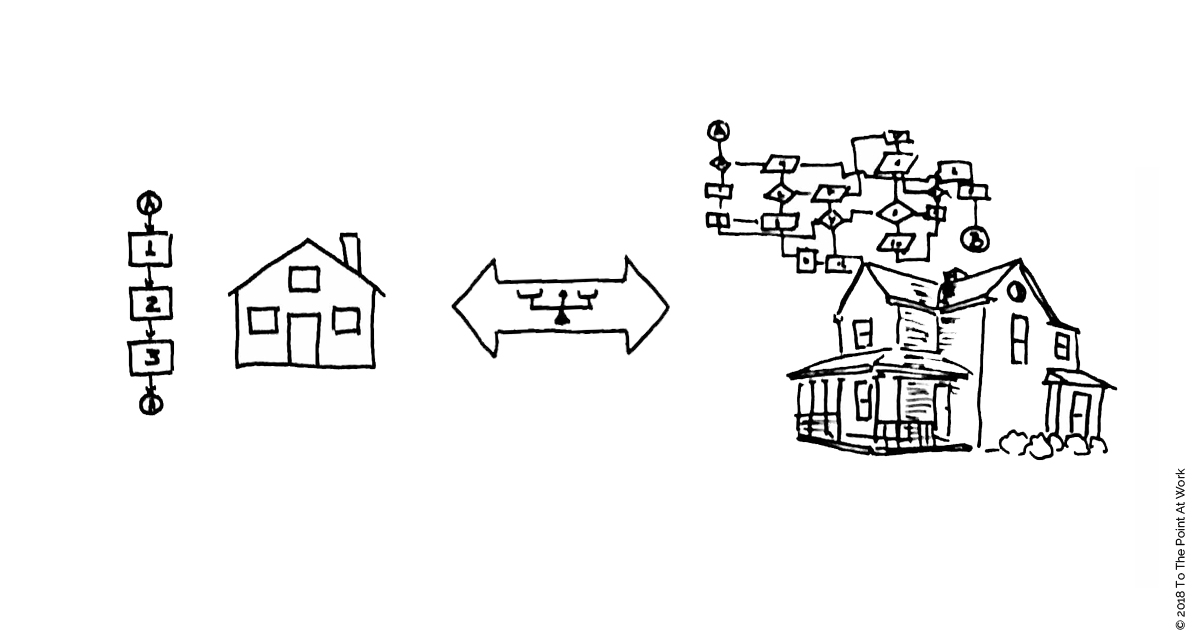

Lack of priorities. In the same way strategies often lack clear priorities. When everything is important, nothing is. It’s like in the two drawings above. On the left side, the focus is clearly on the man. At the right, everything is sharp and every reader can decide differently what to focus on.

2. Be short while embracing the need for detail.

People have little time. Keeping their attention is difficult. So once you have their attention, you’d better be short. We all have tons of information to process. The last thing anyone wants is a long text or a long speech, if it can be done in less time.

“Brevity is the sister of talent.”

Anton Chekhov

Yet your talk, strategy or story needs detail in order to be sharp, solid, convincing, and memorable.

Detail for sharpness

One way to be sharp or precise is to add detail. In the story of global warming “Human activity” becomes far more precise if you add “like burning petrol, coal and wood”. Without detail, your words could be interpreted wrongly. That’s why we use examples in the first place.

Detail for solidity and credibility

You also need to add detail to substantiate and balance your arguments. You can substantiate your claims by adding proof and underlying data. And you can balancing your claims by also mentioning counter arguments. This honesty and integrity will increase your credibility. Of course those details make your talk longer or your document bulkier.

Detail to be memorable and convincing

There is ample scientific evidence that details, even irrelevant details, will make your story more convincing and will help your audience to remember your words.

The Heath brothers, in their book ‘Made to Stick’, cite the experiment conducted by Shedler and Manis in which they simulate two trials. In the case where juries had to decide whether a mother could keep the custody over her child, irrelevant details like “The child has a tooth brush in the form of Darth Vader” can be of decisive importance. They make arguments like “the child brushes his teeth every day” stick stronger in the juries’ minds, and thus influence their decisions. Such experiments have been replicated in many other studies

(Social Psychology, Kenneth S. Bordens, Irwin A. Horowitz (2001), p. 213-14 & Brad E. Bell; Elizabeth F. Loftus, Journal of Personality Assessment, Vol. 49, Issue 6, 1985, Pages 659 – 664.)

Our brains are associative machines: the more associations you can create by adding concrete details, the clearer the message, the stronger the argument and the longer the recollection. But if the text or the speech is too long, the message will get lost in the clutter and you might lose attention altogether.

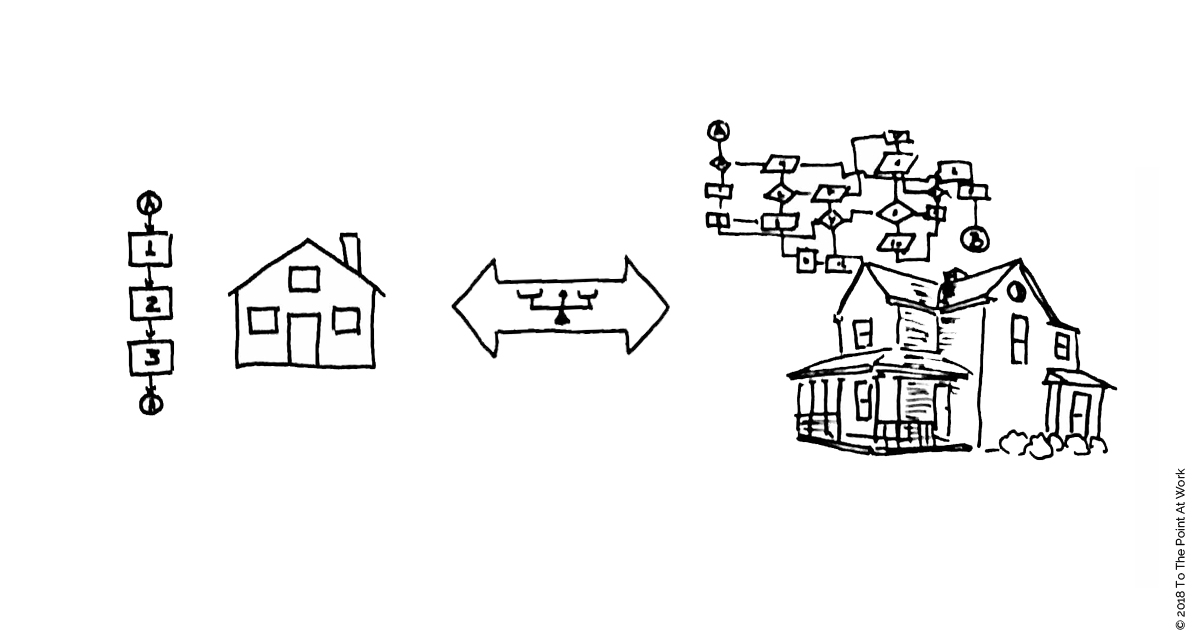

3. Be simple while embracing complexity.

Even though the world is very complex, we like things to be simple. People love simple answers, simple rules, and simple stories. That is because our brain prefers activities with lower effort to activities with higher effort. Simple can be defined as intuitive, plain, and effortless. Something is simple if it requires little intellectual effort to understand. But making things simple is an effortful and tedious work. In other words, simplicity means that the sender of communication is doing the intellectual effort, not the receiver.

“If you cannot explain it simply then you don’t understand it well enough”

Attributed to Albert Einstein.

So, make things as simple as you can, but not simpler. Because if you oversimplify complex things, you lose essential subtlety and nuance. And you may lead people into completely incorrect conclusions. Here’s an example.

In a recent article in “De Morgen”, a leading Belgian newspaper, the journalist claims that local government is completely wrong in its war against drugs. The title of the article was: “Police prioritizes the punishment of drug users over dismantling criminal networks”

For this statement, he uses statistics released by a competent authority. The statistics show that 10% of criminal records are against major drug networks, 20% against dealers and 70% against users. But reality is a bit more complex, because there are many more networks than dealers and many more dealers than users. If there would be 50 users per dealer and 50 dealers per network, the exact same statistic would mean that a dealer has 15 times more chance to get caught than a user and a network has 350 times more chance to get caught. An equally unfair title with the same statistics would be “Police puts 350 times more effort in dismantling net-works than punishing users”. In this case, the oversimplification of the journalist has led to an outright lie. Oversimplified news is very close to fake news.

4. Be steady while embracing change.

Two typical examples: Employees hear from top management that nothing is more important than customer satisfaction, but their direct boss is only focusing on cost reduction to the detriment of the customer. Or the candidate president says that he will focus on deregulating local economy and once elected he is spending all of his time and effort on distant international conflicts.

People are confused when things change or when signals are contradictory. When that happens, they think you have been fooling them. In some cases that might be true. But in most cases it was just unclear information:

Most things in life aren’t steady. The environment changes constantly, so the solutions need to change too. In the first example the company could have come under financial pressure, because of the unexpected weakening of the dollar. Therefor the company might have to reduce expenses in order to protect the quality of the service. In the second case an unexpected distant international conflict might threaten the local economy much more than over-regulation.

“Something that does not change

cannot exist”

Heraclitus – Greek philosopher 535 BC

This problem is inherent to any fast changing environment. In order to be clear, the message has to be constant over time. But if the circumstances change, how can you keep the message consistent?

Often the solution is in searching the right level of abstraction. Rather than only saying what you are doing, also explain why you are doing it. If circumstance change, the ‘what’ may change, but the ‘why’ will remain; You will be more consistent. Simon Sinek explains this principle brilliantly in his book “start with why”. Watch one of the many online videos where he explains the principle.

5. Be solid while embracing uncertainty and emotion.

Of course you want to be convincing and credible. Therefore, your reasoning must be complete and your argumentation balanced with pro’s and con’s. Your thinking must be substantiated with the right data, research or references. You also want to make people feel that you are certain about what you claim.

But there are two issues with being solid. First of all there is always some uncertainty. We cannot predict tomorrow’s world. And you have to be honest about that. In other words you should address the risk element in your statements. This is something that is overlooked over and again in corporate strategies and plans. Those plans are always based on assumptions, but the probability of the underlying assumption is rarely addressed. True strategy should account for multiple scenario’s each with their own probability. And every measurement or forecast should show an error margin.

Secondly, solidity is more than factual, rational evidence. However rational your subject is, it is emotion that will touch people. It is emotion that will makes them remember, or drives them to action. Without emotion there is no decision and there will be no change.

Remember the crisis with Syrian refugees. Already in 2012 the UN reported 200,000 refugees outside Syria. By 2014 the number had grown to 3 Million. But it was the picture of one single toddler ‘Alan’, lying dead on the beach, face down, in a red T-shirt, that ignited a global response in 2015. Statistics about millions of people hadn’t moved governments, but the picture of one little boy did. Because that picture had touched their emotion.

“Success comes not from having certainty,

but being able to live with uncertainty.”

Jeffrey Fry

Edouard (Ed) Gruwez

Send your questions, comments and suggestions to me on ed@tothepointatwork.com

Get in touch

Need more info about how we can help?